An investigation into how America's immigration policies have created a de facto labor underclass, drawing bold parallels to historical caste systems

Introduction: Invisible Apartheid

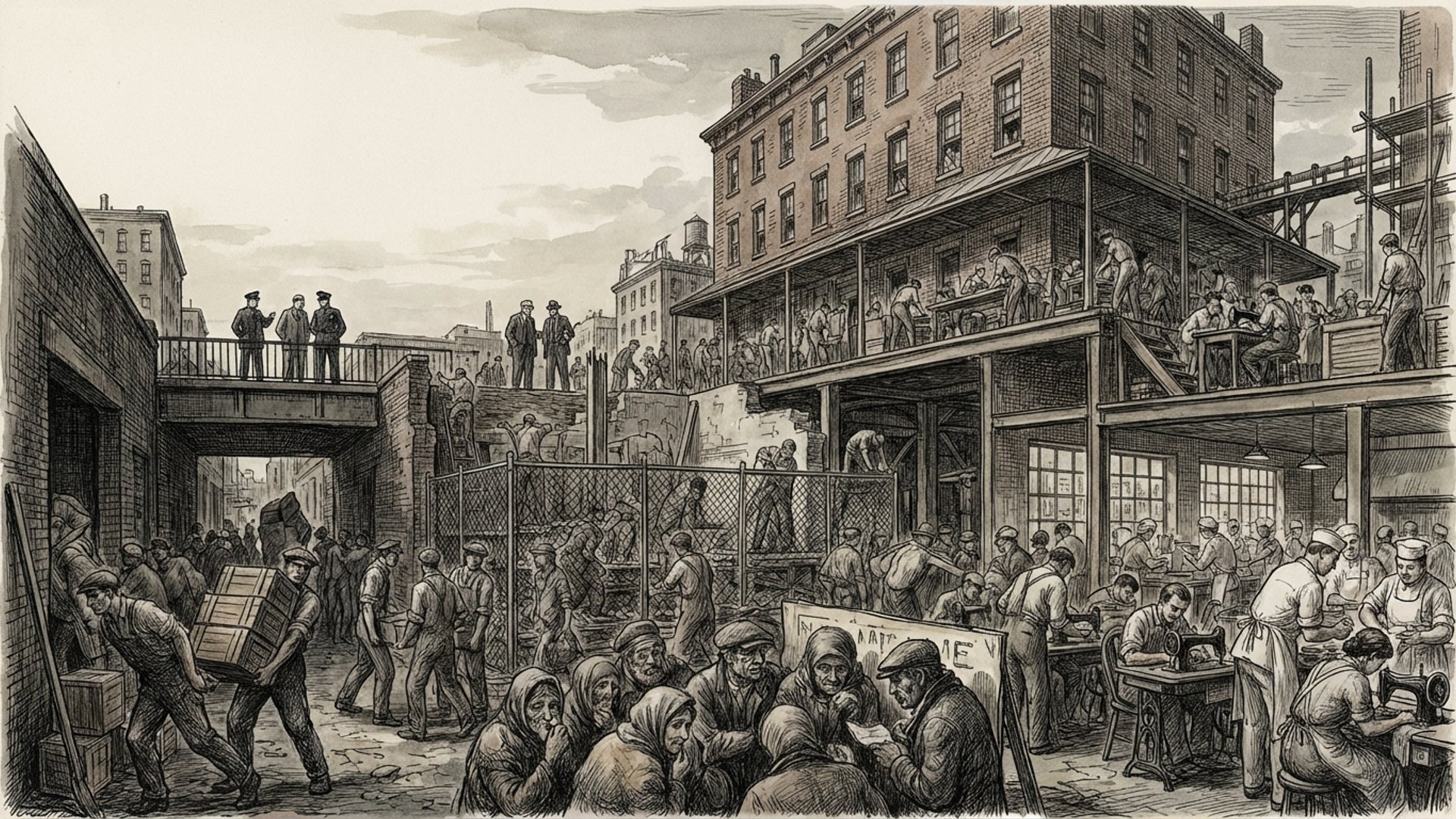

n the shadows of the U.S. economy, millions of undocumented immigrants sustain entire industries while being systematically excluded from the rights and protections afforded to others. Some advocates and scholars have likened this dynamic to a modern-day caste system – even an apartheid in all but name – where a readily exploitable class of workers exists apart from the legal community.

The analogy is provocative but not without merit. Apartheid South Africa, Jim Crow segregation in the U.S. South, colonial labor regimes, and indentured servitude all hinged on a disenfranchised labor force forced to accept dangerous, demeaning work for the benefit of others. Today's undocumented immigrants endure a similar fate: they perform backbreaking jobs under "subsistence wages with little or no time off, and none of the protections or perks that most of us enjoy … a life that is barely a step above slavery."

This article investigates how America's immigration policies have created a de facto labor underclass, drawing bold parallels to historical caste systems, and asks whether the U.S. economy has grown dependent on maintaining this quasi-legal workforce.

A Caste by Any Other Name: Historical Parallels

Undocumented immigrants in the U.S. occupy a status that bears striking resemblance to past systems of institutionalized inequality. Under Jim Crow segregation, Black Americans were legally second-class citizens – exploited as a cheap workforce, denied political representation, and segregated socially. Today, undocumented workers (many of them Latino and Asian) fulfill a parallel role as "the new exploitable 'help'", filling jobs "once reserved for Blacks under the practices of Jim Crow."

The key difference is that this modern divide is drawn along legal status rather than race: by law, undocumented immigrants have "a legal designation that prohibits class mobility", barring them from normal labor protections or political voice. This effectively traps them in a permanent subservient class – or as one academic put it, an "illegal…alien caste" consigned to an "inescapable…subhuman" status.

Apartheid Parallels

Historical apartheid and colonial labor regimes similarly depended on an unfree workforce. In colonial economies, local populations or imported indentured servants were pressed into service with few rights, much as undocumented migrants today feel compelled to accept severe exploitation to survive. In U.S. agriculture, for example, immigrant farm workers are often described as "virtually indentured" servants.

During the apartheid era in South Africa, Black workers needed special passes to work in white areas and had no political representation – a system maintained because it provided industries with cheap, compliant labor. Likewise, undocumented immigrants live under constant threat of deportation, effectively unable to complain or organize. Even allies of undocumented workers implicitly accept that they "occupy a permanent…caste" – a subordinated group tolerated only as laborers. In both cases, the dominant society enjoys the fruits of their labor while enforcing their exclusion from civic life.

Indentured Servitude Redux

Indentured servitude offers another illuminating comparison. Indentured laborers – from 17th-century European servants in the Americas to 19th-century Asian laborers in colonial plantations – were bound to work for years with no freedom to quit, often under harsh conditions. Today's undocumented immigrants are not formally bound by contracts, but many are effectively tied by economic necessity and fear.

Some arrive indebted to smugglers or traffickers, working off those debts under threat – a scenario tantamount to debt bondage. Even without formal indenture, the constant threat of immigration enforcement creates a coercive backdrop. Employers know many undocumented workers dare not quit or report abuse, since contacting authorities could lead to their deportation. This power imbalance – a hallmark of indenture and other coercive labor systems – enables extreme forms of exploitation.

In sum, while undocumented immigrants are not legally enslaved or segregated by race, the practical reality of their exclusion aligns uncomfortably well with these historical labor caste systems. They are a laboring class apart, essential yet officially unwanted – America's "invisible apartheid."

Taxation Without Representation: Paying Into a System That Shuts Them Out

One hallmark of this systemic exclusion is that undocumented immigrants can and do pay taxes, even as they lack political representation and legal rights in the society they enrich. In a historical irony, they live under a form of "taxation without representation" – the very grievance that sparked the American Revolution.

Through mechanisms like Individual Taxpayer Identification Numbers (ITINs) and false or borrowed Social Security numbers, millions of undocumented people dutifully file income tax returns and have payroll taxes deducted from their checks. In fact, undocumented immigrants contribute billions in taxes annually. In 2017, an advocacy analysis highlighted that undocumented people contribute roughly $11 billion in state and local taxes each year and about $13 billion into Social Security – funds they will almost certainly never get back in benefits.

The Social Security Subsidy

Consider Social Security, a program frequently (and mistakenly) thought to be drained by undocumented workers. In reality, unauthorized workers are propping up Social Security. By 2007 the Social Security Trust Fund had received a net surplus of $120–$240 billion thanks to contributions from undocumented workers, who at the time made up roughly 5% of the U.S. labor force. That year alone, unauthorized immigrants paid an estimated $12 billion more into Social Security than they took out, since most cannot claim any retirement or disability benefits.

The chief actuary of the Social Security Administration noted that without these contributions, the system would have hit a persistent shortfall years earlier, as the large Baby Boomer generation began retiring. In short, undocumented workers are subsidizing programs that support American retirees – all the while having no political voice in the system.

Higher Tax Rates Than the Wealthy

Importantly, many undocumented immigrants want to be on the books despite the risks. The U.S. Internal Revenue Service issues ITINs precisely so that people without Social Security numbers can file taxes. Workers use ITINs to report income, signaling a good-faith effort to contribute to society.

This contradicts the stereotype of undocumented people as "tax cheats." In fact, because they often cannot access tax credits or social programs, their effective tax rates can be relatively high. One analysis found undocumented immigrants on average pay about 8% of their incomes in state and local taxes, a higher tax rate than the wealthiest 1% of Americans pay (around 5.4%).

These immigrants are, in effect, stakeholders in the system – funding public coffers – yet they remain civically invisible. They have no representatives, no formal means to voice grievances, and limited legal recourse if their rights (like minimum wage or safety standards) are violated. This fundamental disconnect – contribution without representation – echoes past injustices and underscores the quasi-colonial nature of their position in U.S. society.

Essential Industries, Expendable People

Undocumented immigrants form the backbone of several major U.S. economic sectors – agriculture, construction, hospitality, food processing, and more. These are often low-wage, high-risk industries shunned by many U.S.-born workers, yet critical to the nation's daily functioning. The paradox is that this labor is simultaneously essential and expendable: it is eagerly consumed by the economy but officially disowned and made vulnerable.

Agriculture: The New Sharecropping

Nowhere is the reliance more stark than on America's farms and fields. By the mid-2010s, an estimated 50% or more of U.S. farmworkers were undocumented. Crops from coast to coast – lettuce, strawberries, citrus, dairy – are planted and picked by immigrant hands. Agribusiness lobbyists claim "Americans won't do these jobs," and indeed the work is grueling: "hours of backbreaking work in terrible and often dangerous conditions", for poverty wages and no benefits.

One 2013 investigative report described immigrant farm labor as "imported serfs", noting that even the limited protections in the seasonal guest-worker program are often ignored – big farms prefer hiring undocumented workers precisely because they can be paid less and intimidated more. The result is a farm labor system many compare to the Jim Crow-era sharecropping or worse.

Farm workers today still lack many basic labor rights (federal law exempts agricultural labor from overtime and some safety rules, a "shameful legacy of our slave economy" according to the AFL-CIO). It is telling that when a state like South Carolina passed a law to get tough on illegal immigration, they exempted farm employers from the requirement to verify workers' legal status. Lawmakers tacitly understood that crops would rot without this labor force.

Construction: Building America in the Shadows

Immigrants literally build America, and many of those builders are undocumented. More than 23% of the construction workforce in 2023 was foreign-born, and about half of those were undocumented – meaning roughly 1 in 10 U.S. construction workers is undocumented. They are the ones pouring concrete in Texas heat, hanging drywall in California subdivisions, and rebuilding roofs after storms.

This workforce is so crucial that mass deportations would cripple the housing industry. A recent analysis warned that deporting all undocumented construction workers would deepen the national housing shortage and drive up home prices. Because undocumented labor fills a critical gap: they often do the "lower-skill" but essential jobs (digging, carrying, basic carpentry) that enable higher-skilled trades (electricians, plumbers) to do theirs.

Hospitality: The Invisible Service Class

From hotel housekeeping to dishwashing in restaurants, undocumented workers are the uncelebrated providers of comfort and sustenance. Nationwide, about 9–10% of hospitality and food service workers are undocumented, and in major cities like New York and Los Angeles as much as 40% of restaurant kitchen staffs are undocumented immigrants.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, this became tragically clear: restaurants shed millions of jobs, and a large share of those laid-off were undocumented. These workers had no safety net – barred from unemployment benefits or stimulus checks – despite in many cases having paid into the system for years. Their plight underscored how they are considered simultaneously "essential" and "illegal."

Laws That Punish Workers and Protect Employers

How did such a stark double standard arise? The answer lies in policy choices that aggressively punish the immigrants themselves while letting the employers of undocumented labor off with a wink and nod. U.S. immigration law makes it illegal to hire unauthorized workers, but the enforcement of those laws has been, at best, feeble and inconsistent when it comes to employers.

The Employer Sanctions Charade

The modern era of employer sanctions began with the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) of 1986, which for the first time made it unlawful for employers to "knowingly" hire undocumented workers. On paper, this was supposed to remove the "job magnet" attracting unauthorized migration. In practice, employer sanctions have been riddled with loopholes and seldom enforced.

Employers are required to have workers fill out I-9 forms and provide identification, but false documents are easily obtained and often quietly accepted. Enforcement agencies conduct only spot audits, and prosecutions of employers are extremely rare relative to the scale of the underground workforce. As a result, many businesses operate with an unspoken bargain: present a paper – any paper – and we won't look too hard.

Enforcement Theater

The imbalance in enforcement priorities is stark. The AFL-CIO notes that the United States spends 12 times more money on immigration enforcement than on enforcing labor standards. As the union federation put it, "decades of enforcement-only immigration approaches have prioritized the detention and deportation of migrant families over the protection of workers."

This focus, they argue, has effectively turned immigration policy into labor policy – specifically, a "cheap labor policy". The failure to pass comprehensive immigration reform for nearly 40 years has "created a near permanent subclass of millions of exploitable workers", which the AFL-CIO calls "unacceptable". Yet it persists because it is economically convenient.

In effect, U.S. law has produced a reality where being an undocumented worker is treated as a more serious offense than exploiting an undocumented worker. This inversion of justice has drawn condemnation from human rights observers.

Addicted to a Shadow Economy: Economic Dependency

The uncomfortable truth is that the United States has developed a kind of addiction to undocumented labor. The low prices American consumers enjoy – from supermarket produce to restaurant meals to new homes – are subsidized by the low wages of undocumented workers. Businesses large and small have come to rely on a workforce that can be paid less, not offered benefits, and fired or replaced at a moment's notice.

The Cost of Mass Deportation

Studies attempting to model the removal of all undocumented workers predict severe economic repercussions. One analysis by the conservative-leaning American Action Forum found that a theoretical mass deportation of all ~11 million undocumented immigrants would cause U.S. GDP to shrink by over $1 trillion and would cost the government between $400 and $600 billion just to carry out the removals.

The labor force would contract sharply – by an estimated 6.8 million workers lost – and not enough unemployed Americans would be available (or willing) to fill the void. The result would be labor shortages across multiple sectors, leading to 4 to 6.8 million jobs unfilled, production disruptions, and private industry output dropping by $382–$623 billion almost immediately.

State-Level Experiments

Even short of extreme scenarios, one can observe mini-experiments when states enact harsh immigration laws. Alabama passed an extremely strict law in 2011 (HB 56) aiming to drive out undocumented residents. The immediate aftermath saw farm labor shortages – tomatoes rotting in the fields as migrant workers fled the state – and some construction sites idled. The Alabama agribusiness sector begged for the law's reversal after losing an estimated $11 million in crop proceeds that year due to labor scarcity.

More recently, in 2023, Florida approved a law (SB 1718) with E-Verify mandates and penalties that scared many immigrant workers away. By mid-2023, Florida farmers and builders reported difficulties finding workers; anecdotal videos showed half-empty construction crews and unpicked produce, suggesting the state's economy was taking a hit.

The Limits of Deterrence

Given the evident demand for immigrant labor and the dire conditions driving migrants from their home countries, an important question arises: can anything realistically deter undocumented migration? U.S. policy has oscillated between enforcement crackdowns (to make life harder for unauthorized immigrants) and half-hearted attempts to address "root causes" in migrants' home countries.

Enforcement Escalation Paradox

On the enforcement side, the U.S. has tried a "deterrence through toughness" approach repeatedly – yet people keep coming. Since the 1990s, each escalation at the border (more walls, more patrol agents, high-tech surveillance) has been met with shifts in migration patterns rather than cessation.

As sociologist Douglas Massey famously observed, "Despite these energetic efforts at restriction, immigration from Latin America did not decline but continued apace." Border Patrol funding increased tenfold from 1986 to 2004, and the U.S.-Mexico border became one of the most fortified boundaries in the world. Operations like "Gatekeeper" and "Hold the Line" in the 1990s made crossing far more dangerous – funneling migrants into deadly desert routes.

The immediate effect was counter-intuitive: undocumented migration shifted from seasonal & circular to permanent settlement. Many migrants who used to go back and forth each year decided to stay in the U.S. once they made it through, because returning home and re-crossing had become too risky and expensive. Thus, the undocumented population ballooned from 3.5 million in 1990 to about 12 million by 2006, despite all the crackdowns.

Economic Cycles vs. Enforcement

Empirical research finds that undocumented migration responds more to U.S. economic cycles than to enforcement. When the U.S. economy is booming and jobs are plentiful (for example, the late 1990s or mid-2010s), unauthorized entries and visa overstays increase; when there is a recession or fewer jobs (e.g., post-2008 Great Recession), the net migration from Mexico actually dropped to zero or became negative for a time.

In other words, the magnet of jobs and higher wages is far more influential than headline-grabbing enforcement actions. This suggests that a pure deterrence strategy – making conditions harsher and hoping people won't come – is at best marginally effective and at worst inhumane.

Conclusion: Toward Dismantling the Invisible Wall

Undocumented immigrants in the United States live in a bold contradiction – integral to the nation's economy, yet excluded from its promise. They are de facto members of American communities, but the law relegates them to an ambiguous existence, no more welcome on paper than a century ago's indentured servants or sharecroppers.

This investigative journey has drawn parallels between that reality and some of history's darkest labor systems: apartheid, caste, colonial forced labor, Jim Crow. The comparison is not made lightly. Of course, there are differences in context and degree – but at its core, the common thread is a group of people deemed exploitable and disposable by a system that profits from them.

The Path Forward: Legalization

What would justice and pragmatism entail? Bold, visionary change. Legalization – an earned path to citizenship – is the most straightforward solution. It would immediately eliminate the vulnerability that employers exploit. Legal permanent residents and citizens cannot be threatened with deportation for organizing or asserting their rights. They can demand higher wages, and move between jobs, forcing industries to improve conditions or automate.

The AFL-CIO and most major labor unions now strongly back a broad legalization, seeing it as essential to "lift the floor" for all workers and end the two-tier labor system. As the AFL-CIO wrote, "There is no way to prevent exploitation…until we regularize the status of those currently forced to work in the shadow economy."

Breaking the Silence

Perhaps most importantly, Americans must confront the moral cost of our inexpensive fruits, bargain restaurant meals, and tidy lawns. The low prices hide high human costs. If consumers and voters demand fair labor practices and are willing to pay a bit more to ensure them, political leaders will eventually listen.

The silence around this issue needs to be broken. A system that keeps millions in a perpetual second-class status, working without rights for the benefit of the rest, is not all that far removed from those ugly names in history.

In closing, dismantling this invisible apartheid is not only a matter of justice and human rights; it is about defining what kind of society America wants to be in the 21st century. A bold, self-confident nation should not fear extending rights to those who have earned their place in our communities through labor and love for a better life.

As Jose Antonio Vargas, an undocumented American journalist, reminds us: "Legality is a matter of power, not justice." We have the power to reform the laws and extend justice to this hidden caste of workers. The question is whether we have the vision and will to do so – to replace a system of exclusion with one of empowerment and equality, and in the process, finally align our economy with our ideals.

Sources

- American Immigration Council – Undocumented Immigrants Giving Social Security, Baby Boomers a Big Boost

- Guardian (S. Walshe) – "Field work's dirty secret: agribusiness exploitation of undocumented labor"

- Urban Institute – "Mass Deportations Would Worsen Our Housing Crisis"

- Pew Research Center – "Industries of unauthorized immigrant workers"

- Civil Eats – "Undocumented Restaurant Workers… Stand to Lose the Most"

- ACLU of Southern California – "Because the Law is the Law"

- AFL-CIO – Statement on Border and Workforce (Immigration)

- Human Rights Watch – "Major Victory for Immigrant Workers in the US"

- American Action Forum – "The Economic Cost of Removing Unauthorized Workers"

- Massey et al. – "Undocumented Migration from Latin America in an Era of Rising Enforcement"

This article is part of the Sol Meridian Governance series, examining how institutions shape democratic capacity and social justice.