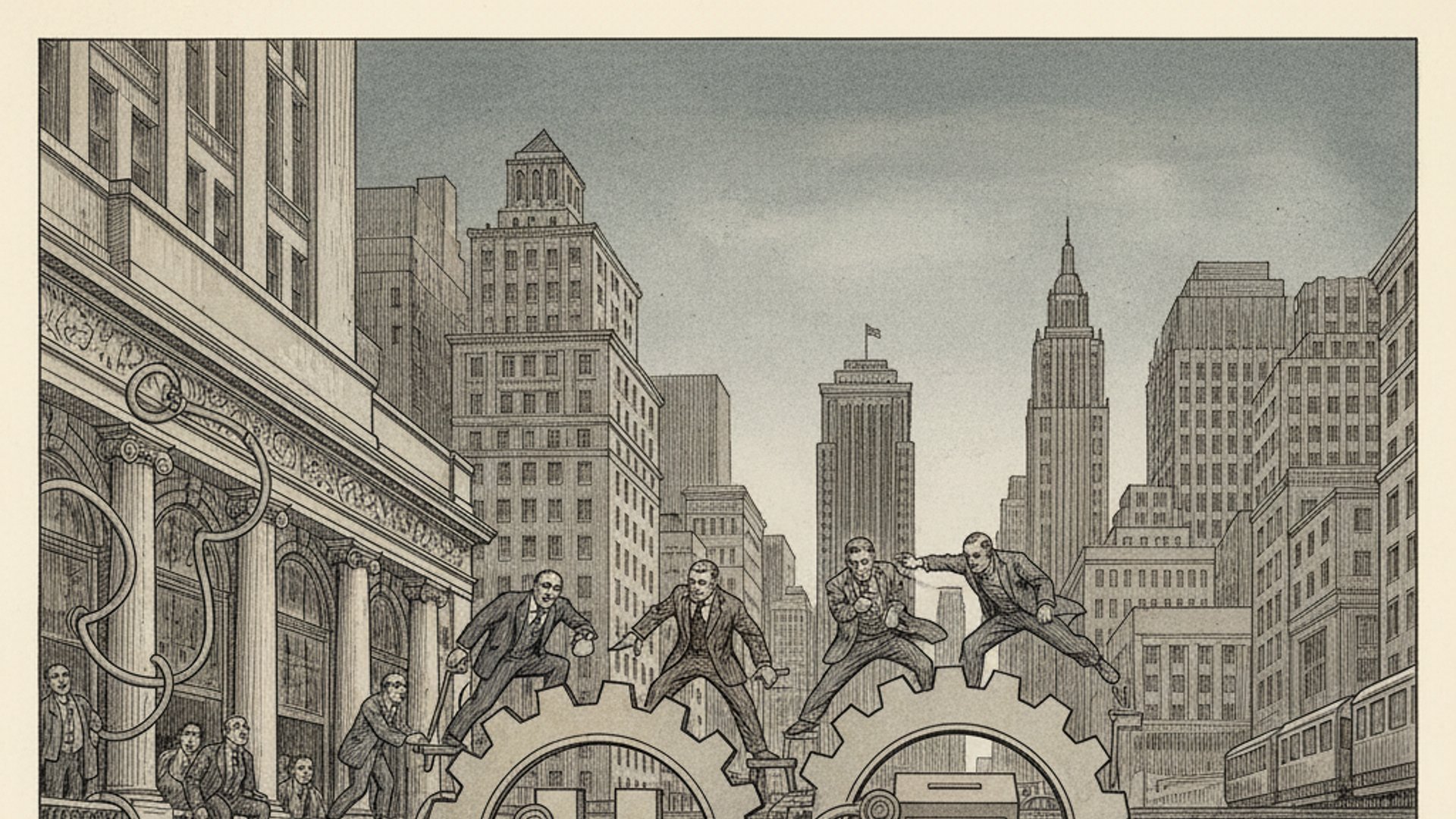

here are corporate deals that feel like weather—massive, impersonal, an atmospheric front rolling in. And then there are deals that feel like a hand on the thermostat: someone deciding, with quiet confidence, who gets heat and who gets frost.

The sudden battle for Warner Bros. Discovery—Netflix on one side, Paramount Skydance on the other—belongs to the second category. On paper it's a contest about streaming scale, studio libraries, debt, and the slow death (or costly afterlife) of linear television. In practice it's also about something less spreadsheet-friendly: whether the American regulatory state can still pretend it adjudicates mergers as if presidents were merely citizens with strong opinions, rather than politicians with enemies, donors, lawsuits, and a taste for leverage.

What makes this fight unusually combustible is not only the size—Netflix's agreed deal for Warner's streaming-and-studio assets versus Paramount Skydance's hostile bid for the entire company, including CNN and the cable bundle. It's the proximity of the bidders to Donald Trump's power system: the Ellison orbit, Kushner financing, Gulf sovereign wealth capital engineered to avoid foreign-investment scrutiny, and a White House whose relationship with major media has been increasingly transactional.

So yes—this is about HBO. But it's also about what HBO means in a country where "approval" can start to sound like a favor, and "public interest" can become a phrase you say while the real conversation happens elsewhere.

I. Two Bids, Two Maps of Power

Let's state the chessboard cleanly.

Netflix's deal is framed as a targeted acquisition: take Warner's Streaming & Studios—the crown jewels, the intellectual property, the production machinery, the subscription engine—and leave behind the creaking "Global Linear Networks" carcass (the cable channels whose economics are collapsing in slow motion). This structure matches Warner's own recent internal logic: separate what grows from what shrinks.

Paramount Skydance's hostile bid is maximalist: buy the whole organism—studio, streaming, and the linear networks, including CNN and Discovery. Paramount argues it delivers more cash to shareholders and more "certainty" than Netflix, while also claiming that Netflix will run into a longer antitrust slog.

Even if you ignore politics, these are fundamentally different theories of the media future.

Netflix is saying: "The future is one global subscription-and-production super-engine. The rest is runoff."

Paramount is saying: "The old bundle still prints money for long enough that it's worth owning—and it can be used as ballast while you rebuild streaming."

Now add the political dimension and the bids become maps of influence.

Because Netflix buying "Streaming & Studios" is, by design, a way to acquire the entertainment crown while avoiding the most politically radioactive assets: CNN and other legacy-news-adjacent properties. Paramount's bid does the opposite: it invites a fight over the most sensitive thing in American capitalism—control of narrative infrastructure—at the same time that the White House has shown a willingness to treat media organizations as adversaries to discipline, or as instruments to tame.

II. Why Trump Matters Here, Even If He "Shouldn't"

In a civics textbook, the President does not "approve" mergers like a medieval king approving marriages. Regulatory bodies do—primarily the Department of Justice (Antitrust Division) for competition, the FCC for certain license transfers, and sometimes CFIUS when foreign investment triggers national-security concerns.

In reality, the President shapes the incentives and the personnel of that apparatus. Presidents appoint. Presidents signal. Presidents punish. And if you're a corporation attempting a deal that might be delayed, blocked, or conditioned, you don't just study statutes—you study the temperament of the person standing behind the system like a stage manager.

In this Warner battle, Trump has reportedly inserted himself rhetorically: warning about monopoly risks and suggesting he'll be involved in the approval process. That matters for two reasons:

- It invites bidders to treat the regulatory process as political terrain.

- It creates a market for "alignment." Not necessarily bribery—often something blurrier: editorial posture, personnel changes, strategic "goodwill," private assurances, friendly intermediaries.

The United States has always had some version of this. But the current moment has an extra ingredient: a thick fog of litigation and retaliation between the Trump ecosystem and major media companies.

That fog is not abstract. Paramount, for instance, has been living inside a highly controversial settlement with Trump connected to a "60 Minutes" dispute—an episode that even an FCC commissioner criticized as a dangerous precedent and described as a "desperate move," warning of the press-freedom implications.

Once a president demonstrates that pressure campaigns against media can yield settlements, resignations, and corporate recalibrations, every subsequent merger starts to look like a negotiable document—not with the public, but with power.

III. "Corruption" Without the Cartoon Villain

The honest way to talk about modern institutional decay is not as a single crime, but as a spectrum of capture.

A widely used definition—Transparency International's—is "the abuse of entrusted power for private gain." That definition is useful precisely because it's not limited to brown envelopes. It includes behavior that is "legal" yet corrosive.

Four Layers of Corruption

Think of them as geological strata.

| Layer | Definition | Application |

|---|---|---|

| A: Criminal | Quid pro quo bribery (18 U.S.C. § 201) | Something of value given with intent to influence an official act. Hard to prove; absence of proof ≠ absence of rot |

| B: Ethical | Conflicts of interest and inducements | Not "illegal bribery," but designed to please those who can smooth the road: donors, allies, family members |

| C: Institutional | Capture of the referee | Slow conversion of regulators into concierge staff. Enforcement becomes selective. Certainty becomes a privilege |

| D: Epistemic | Control of the story | Power wants not only favorable decisions but favorable interpretations. Discipline narrative institutions until they preemptively accommodate |

The Warner battle touches every layer. Not necessarily as proven crimes—but as incentives, structures, and reputational pressures.

IV. The Paramount Bid's Political Architecture: Ellison + Kushner + Gulf Capital

Paramount Skydance's hostile bid is remarkable not only for its size but for the signature of its financing coalition.

Public reporting and filings describe a package involving the Ellison family and major backers including Jared Kushner's Affinity Partners, alongside Middle Eastern sovereign wealth funds.

Two details matter because they show how finance is now engineered around politics:

- Tencent reportedly withdrew from the financing to avoid triggering national-security scrutiny, according to an SEC filing described by AP.

- The sovereign funds—Saudi, Abu Dhabi, Qatar—were described as relinquishing managerial participation rights to reduce the odds of a CFIUS review or other scrutiny.

This is not how normal corporate America talks when it's merely buying a studio. This is how corporate America talks when it anticipates a political and regulatory gauntlet—and designs the deal as a diplomatic object.

And then there's the human wiring.

Larry Ellison is not just a billionaire. He's a political actor in the modern American sense: donor behavior, proximity to Republican circles, and a family media footprint that has been expanding.

Kushner is not just a financier. He is, by blood and by history, a conduit—someone whose involvement doesn't merely add capital, but adds access.

That's the structural reason critics call these arrangements "corruption" even when prosecutors are nowhere in sight: they are attempts to purchase certainty from a system that is supposed to be impartial.

V. Netflix's Bid: Less Politically Explosive, But Not Politically Innocent

Netflix's approach looks cleaner because it avoids CNN. That matters. It reduces the obvious conflict: a president angry at news networks is less directly implicated in a deal that doesn't transfer a major news brand.

But Netflix's bid still runs into two kinds of scrutiny:

Competition policy. A combined Netflix + Warner Streaming/Studios entity could concentrate enormous market power in global streaming and content production—enough that observers are already framing it as a potential "Big Streaming" monopoly issue.

Political opportunity. If Trump wants to posture as anti-monopoly while remaining friendly to donors and aligned owners, he can. He can slow one deal, accelerate another, demand concessions, or simply use uncertainty as leverage.

The point is not that Netflix is "safe." The point is that Netflix is a cleaner canvas for political bargaining because fewer people will notice the fingerprints.

VI. Why Trump's Self-Interest Could Prefer Paramount—Especially If CNN Is the Prize

Now we get to the uncomfortable part: how Trump might evaluate these options "based on what is good for him."

You don't need mind-reading. You need pattern recognition.

Trump's relationship to CNN is not subtle. He treats hostile coverage not as journalism but as political action—something to be punished, discredited, or domesticated. In that worldview, changing CNN's ownership is not a mere business outcome; it's a strategic victory.

Paramount's bid includes CNN and other linear networks.

Netflix's deal, as described, does not.

So the Paramount deal potentially offers something Netflix cannot: the ability to reshape one of Trump's most symbolically hated media institutions under new ownership, perhaps folded into a broader news strategy (there has been reporting about integration concepts involving CBS News and CNN as part of the overall corporate logic).

Even if Paramount never explicitly promises editorial changes, the mere possibility creates leverage. And if you believe in "fear of power" as a governing force, the mechanism is obvious:

- Executives anticipate what the White House wants.

- They overcorrect.

- They call it "risk management."

That is how independent institutions are weakened without a single explicit command.

VII. The Regulatory Levers: Where "Approval" Becomes a Bargaining Chip

Here's where the machinery matters.

Antitrust (DOJ)

Both deals invite antitrust review. Netflix's deal invites a long one; even Paramount's own arguments emphasize that Netflix faces a 12–18 month path. In a politicized environment, "time" is not neutral. Delay can be punishment. Speed can be reward.

CFIUS (Foreign Investment)

CFIUS is authorized to review certain foreign investment transactions for national security risk, and at its recommendation the President can suspend or prohibit transactions. Paramount's reported structuring—removing Tencent, limiting governance rights for sovereign funds—reads like a preemptive attempt to avoid that lever being used at all.

FCC (Broadcast Licensing)

FCC authority is triggered by transfer of control of broadcast licenses and is governed by a "public interest" standard. This matters more for Paramount's existing broadcast footprint (CBS) than for Warner's cable networks; and in 2025 the FCC's posture has already been entangled with political controversy around media disputes and settlements.

So when people say "Trump will approve one or the other," they're not claiming he signs a merger parchment with a wax seal. They're describing something more banal and more dangerous: the President can shape the conditions under which the decision is made, and corporations behave accordingly.

VIII. "Both Sides-ism" in Merger Coverage: Why This Case Is Not Symmetrical

A predictable media reflex is to narrate this as: "Two giants fight; regulators decide; politics is noise." Another reflex is "both sides-ism": if you mention political pressure on one side, you must mention it on the other, as if symmetry were a form of objectivity.

But not all pressures are comparable.

A president who lies daily about material matters—elections, prosecutions, constitutional events—creates a political climate in which truth becomes an aesthetic choice rather than a civic obligation. In that climate, a newsroom error is treated as a hanging offense, while presidential falsehoods are treated as weather.

Now translate that logic to mergers:

- If the President can extract settlements or public humiliations from media companies, then merger review becomes a quiet stage for coercion.

- If the President can threaten "monopoly review" selectively, antitrust becomes a rhetorical weapon rather than a policy.

That is not "politics in business." That is business as a subordinate province of politics, where the ruler's interests are treated as a variable in corporate valuation.

IX. What Is "Good for the Country" Here?

Let's grant, for a moment, the fantasy that regulators could act like neutral engineers. What would the public-interest test look like?

A) Competition and Consumer Welfare

- Netflix + Warner Streaming/Studios could dominate subscription streaming and content pipelines, potentially affecting pricing, licensing, and creative labor markets.

- Paramount + Warner whole-company consolidation could reduce competition across film, TV, streaming, and advertising markets, while concentrating legacy news assets in fewer hands.

B) Media Pluralism and Democratic Resilience

The danger isn't only price. It's the narrowing of narrative infrastructure. In healthy democracies, major news institutions should not feel like they need political patrons to survive.

C) National Security and Foreign Influence

The presence of sovereign wealth financing—however structured—creates questions about governance, influence, and reputational risk. The fact that financiers engineered away governance rights to avoid scrutiny tells you they know the anxiety is real.

D) Institutional Integrity: Can the Referee Still Referee?

A country can survive a big merger. It cannot easily survive the normalization of "deal approval" as a presidential favor.

X. The Trump-Aligned Ecosystem Around the Deal

Based on current reporting:

| Actor | Role | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Ellison family | Paramount bid backers | Larry Ellison's donor activity and Trump proximity widely discussed |

| Jared Kushner / Affinity Partners | Financing partner | Son-in-law conduit; involvement adds access, not merely capital |

| Gulf sovereign funds | Saudi, Abu Dhabi, Qatar | Governance rights reportedly constrained to limit CFIUS scrutiny |

| Tencent | Withdrew | SEC filing described departure to avoid national-security review |

| Regulatory context | Prior Paramount-Trump settlement | FCC commissioner called it "dangerous precedent" for press freedom |

The story isn't "a villain roster." The story is that the structure itself—which donors are nearby, which family members finance, which foreign funds are engineered into the deal—creates a kind of gravitational field. Once it exists, it doesn't require explicit instructions. It merely requires everyone to keep acting like adults who understand incentives.

XI. The Core Corruption Claim, Stated Carefully

So is this "corruption"?

If you mean prosecutable bribery, we don't have public proof of a quid pro quo. That is the honest statement.

If you mean abuse of entrusted power for private gain, the risk is not hypothetical. It is baked into the incentives:

- A President who publicly signals involvement in approval.

- A bidder coalition that includes the President's son-in-law as a financier.

- A recent history in which a media company's settlement with Trump was framed by at least one regulator as a press-freedom problem tied to merger approval dynamics.

- A financing structure carefully arranged to avoid foreign-investment scrutiny while leaning on politically connected capital.

In political-science terms, that's what corruption looks like when it wears a suit and speaks in compliance language.

XII. The Forecast: What Happens Next, and What the Country Should Watch

The next phase won't be decided by who writes the best press release. It will be decided by:

- whether antitrust review is conducted as a real inquiry or a political theater;

- whether "public interest" is interpreted as public welfare, not presidential comfort;

- whether CNN (and other news assets) are treated as civic infrastructure, not spoils;

- whether foreign capital questions are handled transparently rather than used as selective weapons.

The real tell will be the pattern of the process:

- sudden speed for one bidder, endless delay for another;

- regulators speaking in unusually personal moral tones;

- editorial and personnel changes that occur "for business reasons" right when approvals are pending.

That is how the modern state announces itself: not with decrees, but with timing.

References & Source Notes

Paramount Hostile Bid:

- Reuters: Paramount hostile bid details and filing context; financing partners; process timeline

- Financial Times: Paramount gatecrashes Netflix-WBD deal; antitrust timelines; financing structure and banks

- AP: Tencent withdrawal; sovereign funds giving up governance rights to avoid scrutiny

- The Guardian: Paramount bid overview; political ties and concerns

Regulatory Framework:

- U.S. Treasury: CFIUS authority and purpose

- Congressional Research Service: presidential power to suspend/prohibit transactions at CFIUS recommendation

- FCC public-interest materials (broadcasting guidance)

- DOJ Criminal Resource Manual: federal bribery framework (18 U.S.C. § 201)

- Cornell LII: text of 18 U.S.C. § 201

Political Dynamics:

- Reuters: FCC commissioner critique of Paramount settlement with Trump; press-freedom implications

- Business Insider: Ellison appeal to WBD shareholders; political attention; Trump comments

- Washington Post: Trump library plans, settlements funding narrative, secrecy concerns (context for media/power dynamics)

Corruption Framework:

- Transparency International: definition and framing of corruption