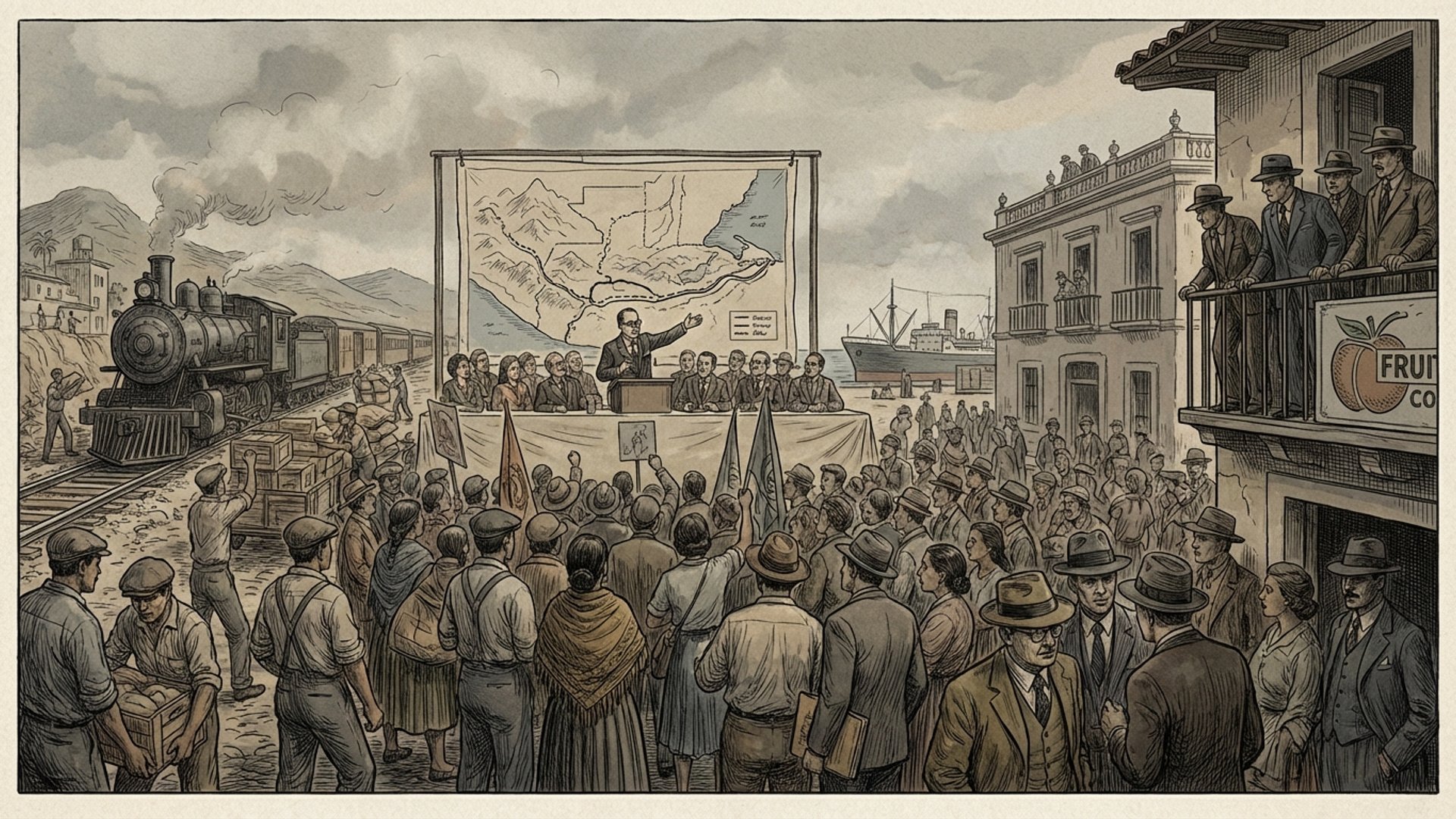

Thesis. Jacobo Árbenz did not try to build utopia. He tried to build a country that could set its own prices. His program—land reform backed by logistics—attacked the chokepoints that kept Guatemala poor: a foreign‑owned port, a foreign‑owned railway, and idle estates that treated peasants as labor reserves rather than citizens. The plan worked on paper and began to work on the ground. It also assembled a coalition against him powerful enough to end a decade of democratic reform. This is the story of the "Ten Years of Spring" as infrastructure politics: who controlled the road to the sea, who set the value of land, and how a small republic learned that spreadsheets can start wars.

⸻

I. A Country Priced From Abroad

y the late 1940s Guatemala exported coffee and bananas along a single corridor: rail to Puerto Barrios, ships of the Great White Fleet, and rates set by the same conglomerate that grew, carried, and sold the fruit. United Fruit's affiliate, the International Railways of Central America (IRCA), controlled the tracks. United Fruit controlled the docks. The monopoly was not subtle; it was a map. If you wanted to move goods, you passed through a gate someone else owned. Prices traveled as instructions.

After the 1944 fall of Jorge Ubico, voters elected Juan José Arévalo and then Jacobo Árbenz. They did not inherit a developmental state; they inherited a tollbooth. Árbenz read the landscape the way an engineer reads a bottleneck. If you cannot change your prices, you do not have a policy. He chose two levers: redistribute idle land to families who would make it productive, and break the transport monopoly that made even productive land dependent on a private corridor to the sea.

⸻

II. Decree 900: Turning Idle Land Into Capital

In June 1952, Congress passed Árbenz's agrarian reform—Decree 900. The law targeted uncultivated land on large estates, offered compensation in long‑term bonds based on declared tax values, and transferred plots to organized peasant committees. The measure did not abolish private property. It forced property to behave like property: use it or sell it to the nation at the price you told the taxman it was worth.

Peasant leagues formed; surveyors arrived; titles moved. Indigenous communities, dispossessed since the conquest, began to see deeds with their names. The reform had a bias toward the modest: small plots to many families, not vast state farms. Output rose where fallow fields turned green. Reformers believed that once families had land and security, credit and cooperatives would follow. A different country began to flicker at the edges of the old one.

Then the numbers touched a nerve. When the government applied Decree 900 to United Fruit's idle acreage, it valued compensation at the assessment the company itself had filed to minimize taxes. The bonds matched the paper trail. On paper the logic was clean. In Washington the logic looked like a challenge.

⸻

III. The Atlantic Corridor: Building Out of a Monopoly

Land without access remains a promise. Árbenz moved on the second lever: the road and the port. The Carretera al Atlántico—the Atlantic Highway—would run from Guatemala City to the Caribbean, shadowing the railway and cutting the rate‑setting power of the IRCA. A new public port at Santo Tomás de Castilla would compete with Puerto Barrios, where United Fruit and its fleet set the terms. The state would not forbid private transport; it would build a second path.

The plan was plain republican economics. Open a rival corridor. Break a monopoly by routing around it. Lower the cost of moving coffee, corn, and machinery. Raise the price of independence.

Construction began. Engineers laid out grades along the Motagua valley. The port plans advanced on a site with a colonial name, Matías de Gálvez. Contracts moved slowly in a poor country; the strategic intent did not. Every kilometer poured was a change in bargaining power.

⸻

IV. The Counter‑Coalition: Company, Cables, and Cold War

United Fruit fought back with the tools it knew best: lobbying, litigation, and narrative. Executives and lawyers argued that compensation was confiscation; they pressed their contacts in the U.S. government; they funded public‑relations campaigns that recoded land reform as communist seizure. In a Washington where the Dulles brothers held power—one at State, one at CIA—and where anticommunism set the temperature of every room, the campaign found warm air.

Security officials saw more than a farm law and a highway. They saw a left‑leaning government in a corridor that touched the Canal, a reform movement with unions at its back, and a public leader who refused to retreat. The analysis folded logistics into ideology. A domestic monopoly became a strategic threat. Planning turned into a case file.

⸻

V. PBSUCCESS: How to Unbuild a Program

The covert operation that followed—code‑named PBSUCCESS—did not rely on a superior army. It relied on noise. The CIA organized a small proxy force under Carlos Castillo Armas, broadcast fabricated battlefield reports over "Voice of Liberation" radio, flew a handful of airplanes to bomb and strafe, and nurtured the perception that the Guatemalan Army would not hold. In June 1954, the perception became policy. The high command pushed Árbenz to resign. He left the National Palace with his boots on and his plan half built.

The new regime reversed the heart of Decree 900. Land returned to old owners; peasant leaders faced jail, exile, or worse. The Atlantic Highway kept going—economics made it useful even to the men who toppled its author—but the logic behind it died. A public port at Santo Tomás would eventually open years later, shorn of the social architecture that originally framed it. The country kept the concrete and lost the covenant.

⸻

VI. After the Coup: The Bill Comes Due

What vanished in 1954 was not only a presidency. It was a sequence. Land titles, credit cooperatives, feeder roads, agronomy teams, a port where the customs officer wore Guatemala's badge—these were steps in a staircase that would have lifted smallholders into markets as producers, not as surplus labor. The staircase was kicked away in the name of stability. The cost arrived later as a civil war that lasted a generation and a countryside that learned to distrust maps.

The coup also taught a maxim that planners still ignore at their peril: when you attack a concentrated rent, you inherit its enemies. Árbenz did not expropriate United Fruit's ships or warehouses; he taxed their story. He insisted that the value on the tax form bind the value in the bond. Accounting became politics; politics became regime change.

⸻

VII. What the Program Actually Tried to Do

Strip the slogans and the program looks modest:

- Move idle land into use with compensation at declared value.

- Open a second corridor to the Caribbean to lower logistics costs and erase a monopoly toll.

- Build a public port to set a benchmark for fees and service.

- Use bonds and time instead of seizures and shocks.

- Tie peasant gains to national prices rather than to a patron's goodwill.

The most radical feature was not expropriation; it was competition. The state would compete with the gatekeeper on the coast and let producers choose the cheaper path. Even conservative economists recognize the power of a benchmark public option to discipline a private monopoly. That is what Árbenz built toward before he was told to stop.

⸻

VIII. Lessons for Planners and for Small Republics

Target the chokepoint first. If one company sets your transport price, build a road and a port even before you build a story. Access is policy.

Keep compensation legible. You can survive ideological attacks longer than you can survive claims of arithmetic bad faith. Árbenz's tax‑value standard was legible; it also made a rich enemy.

Treat narrative as an infrastructure. Radios and rumor are pipes. Your maps will not hold if your story does not.

Expect extraterritorial politics. If reform dents an overseas rent, you are negotiating abroad whether you intend to or not. Build allies and redundancy before you break the first gate.

Institutionalize what you can, quickly. Pour the road; draft the port charter; push titles out of ministries and into pockets. Concrete and paper can outlast a cabinet.

⸻

IX. Coda: The Road and the Sea

On the Caribbean side of Guatemala a public port now works where a private monopoly once stood alone. Trucks roll down an Atlantic highway that began as a line on a reformer's desk. The country kept those structures because they made economic sense even for men who opposed the man who ordered them. That is the quiet victory inside a loud defeat. Infrastructure remembers.

What Guatemala lost was the coalition that could have turned access into dignity at scale. That loss took decades to count. If the next reformer studies Árbenz, they should study him as an engineer of bargaining power: a leader who tried to make prices local and who learned too late that the shortest road to the sea runs through other people's maps.

This analysis examines Jacobo Árbenz's 1951–1954 reforms as infrastructure politics: an attempt to break transport and land monopolies that was stopped by a CIA-backed coup. Part of the Sol Meridian series on Latin American development, U.S. intervention, and the political economy of planning.